A Lesson in Creating More and Worrying Less

I have been writing music for 20 years and I’m still uncovering truths that shake me to my core and change everything about how I create. Sometimes these thoughts take years to unravel, starting with an obsession over some artist or style that becomes clearer to me as I slowly unpack it. For a long time, my mind felt stuck comparing two somewhat opposite composers: Thelonious Monk and Claude Debussy. Monk was pure American Jazz from the 50’s, complex and difficult to listen for long periods yet so trail-blazingly beautiful in moments. Debussy was a French composer working closer to the year 1900, pioneering an idea of musical impressionism that has stayed with me since I learned it, swirling around my head like an eddy until eventually clarity came crashing in.

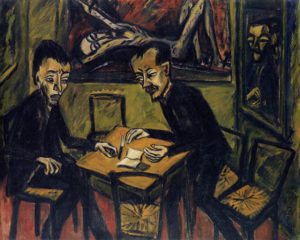

Impressionism was an art movement characterized by the lightest of touches and a dedication to the hard-to-understand minutia. A direct reaction to the bold colors and shapes of German Expressionism, French Impressionism instead sought to capture life as a shades of similar color.

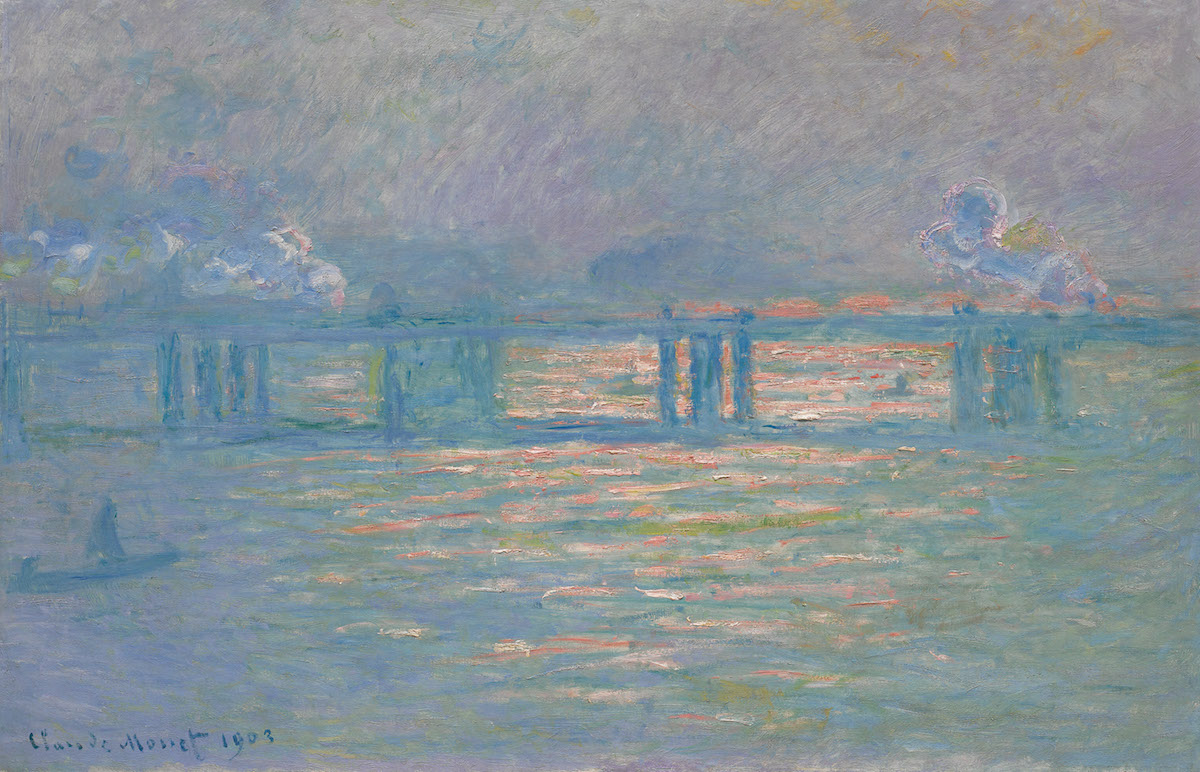

Like this beautiful work from Monet, there is this sense of infinite nuance within the same shade. The typical lines that delineate a background from the foreground are erased, and with it, the expectations we place on form to guide our understanding. What we are left with is not something shapeless, but definitely less certain, and more reliant on the audience’s perspective to give it meaning.

Musically, Debussy chased this aesthetic idea celebrated by contemporaries like Monet. Nuages (or Clouds) for example, mixes moments of grand musical clarity with confusion, occasionally striking such a beautiful progression of chords that all you want is to experience more of it; to ride the wave of melody towards some great place or conclusion. Instead the melody and tempo return you to a place of undefined chaos and you are left with just the memory of what moved through you, what you thought you might have heard. Debussy himself described the sound as “the immutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading away in grey tones lightly tinged with white”.

I believe Debussy understood that our most fundamental sensations cannot not exist separately. In order to understand these moments of intense beautiful purpose, they have to be accompanied by uncertainty. This is basic Taoism at its core. How could one know the concept of happiness without sadness, how could one understand true musical beauty without first being subjected to a little confusion and disarray? Impressionism instilled in Debussy an understanding of subtle nuance, and like Monet, he used these nearly infinite shades of tonal color to construct his masterpieces, and vague musical structure to obfuscate the true sensations. As important as the swelling and beautiful melodies were, the music was just as much defined by what wasn’t as what was.

For Monk too this idea was important, even though he lived 50 years later and as far from the French aristocratic art scene as one could probably be. In a remarkable track like Solitude, we can hear the full genius of this thinking on display. There is a straight-forward melody to this Duke Ellington piece (one any well trained Pianist could bring life to) but for Monk, merely a rough road map. Instead, he introduces these complex chordal vamps, pinching together notes that would make lesser visionaries wince at the audacity. In his time, some called him “the elephant on the keyboard”, misunderstanding that the point was exactly to celebrate those uncomfortable notes. They introduced tension he could take his time resolving and a layer of complexity few could duplicate or understand.

Like Debussy, Monk expected us to search for the nuance in his pieces; listen through the uncertainty for those moments of immense satisfaction when the melodic or rhythmic tension gave way to clarity. However, unlike the longer-winded Debussy, Monk could squeeze these moments into a bar, a phrase, or a mere second of music. Part of this was pure virtuosity, while Debussy was a brilliant composer, Monk was a born pianist whose skills were iron forged in the fire of constant jam sessions throughout the 40’s and 50’s, but equally important was the rise of Jazz and subsequent change in how we saw dissonance. Separated by decades and continents, both composers believed moments of pain were necessary for moments of pleasure, moments of banality in exchange for brilliance.

I was always a melodic perfectionist in search of the most satisfying musical moments; but the importance of times where I’d missed the mark was profound realization for me. Not only did things not need to be perfect… it was better if they weren’t. There was character and texture to both mistakes and the planned moments of chaos that proved essential to the process of crafting beauty. More importantly, those satisfying moments could not exist without the parts I might consider dull, transitional, or unpleasant to the ear.

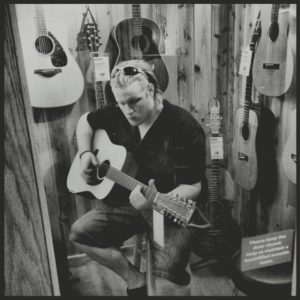

Take a track like “Going Home” from my first album. That was a song spent chasing some type of profound, musical grandeur (or I hoped at twenty). My solution to capturing this sensation was to create simple, muted verses with a vocal just a step above a whisper. When the chorus comes in, it’s much bigger, with long vocal notes that I could often double or triple up when I played with others; a stylistic borrowing from Bluegrass. The softness of the verse allowed this spiritual like chorus to stand out and the sensation of longing to overwhelm your initial expectations. On the road, this has always been a crowd favorite, and I believe part of the reason is that simple balance.

It negotiates that understanding of balance in its own way, but there is little effort to surprise you or to present a counterbalance. It was not written to make you think, but to relax, enjoy, and maybe encourage you to buy a few albums on my way out of town. I still love to write songs like this, and they’re great for live work or chilling around a campfire, but all artists must evolve as well. How we do so is in our hands.

2009

2019

Let’s look at a track I created once I had a better understanding of the principles I was playing with. Kitty was one of the few songs I wrote directly for a partner, and it’s meant to reflect the often confusing and multi-faced parts of loving someone else. The violent beginning uses aggressive synths, pushing the listener back a bit before giving away to a very sultry and raw drum part. We then fade into this sensuality and we’re eventually rocked back by those violent elements again. As the track wanes, the sounds meet and blend into each other, presenting these moments of pain and pleasure, confusion and understanding, frustration and satisfaction.

There are sounds here that I see as the near perfect rendering of what I had hoped, and other moments I had to accept as passing through or necessary to achieve that concept. The drums were everything for me, the story of intensity I wanted to tell, and the sensual punch they deliver as they fade in from these scenes of violence was exactly what I’d hoped.

If you’ve made it this far, read my nearly 1200-word essay on Monk, Debussy, and using their principles to adopt a new mindset about creation…bravo. You’re either the best fan ever or a fellow musician/producer. The takeaway is this: the greats understood that you’re not always giving your audience what they want, or even what you want. Often, you must create the sounds of uncertainty that will bring life to your dynamism, create (like an author) both the mundane world around the character as well as your heroic protagonist. That is how one tells a story with music that can transcend and enrapture: through mastery of both tension and release, use of the million shades of a tone, and an acceptance for the background that must be established for melodies to burst forth into being.