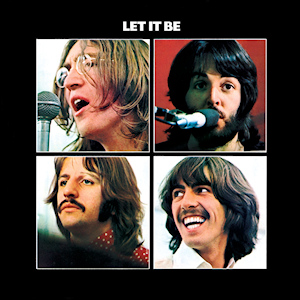

The Beatles 1970 Let It Be, their 12th and final album, finds the band in true form with the songwriting of McCartney and the iconic recorded rooftop performances, both of which capture that unique essence of early Beatles.

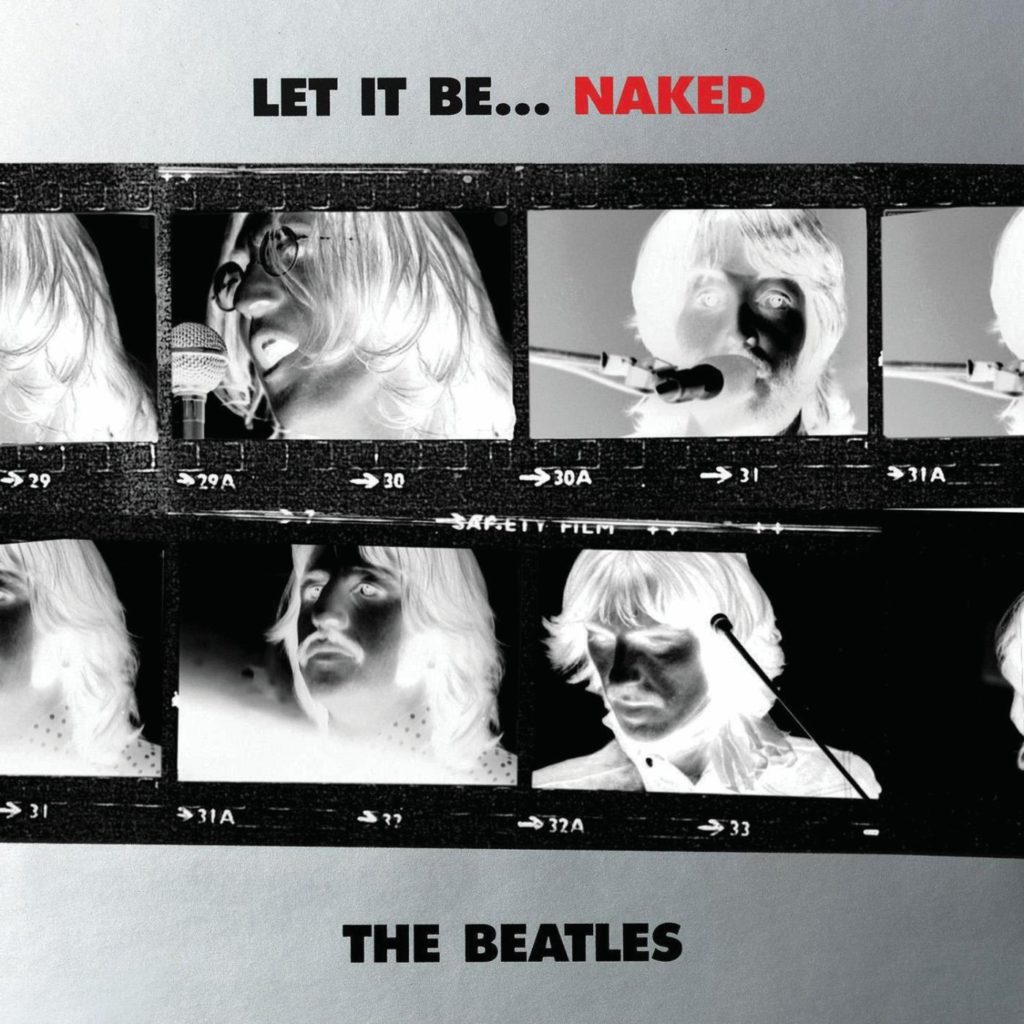

Let It Be was recorded in England at Apple Studios, then finalized and assembled separately by American mega producer Phil Spector. While the album was a huge commercial success, McCartney has long complained that it was a bastardized version of his original vision. In 2003, McCartney finally released Let It Be…Naked, a new production that rebuked Spector’s touches and a returned it to what he had originally imagined.

I don’t think it’s unfair to start this by saying: Spector was ultimately the benefactor of a cultural generation with a much lower barrier of entry, despite some of his notable additions to the producer’s cannon.

Finding his way into the biz after a stint with a 50’s doo-wop group The Teddy Bears, his popular at-the-time production works are mostly absent from the larger culture of today because in the cacophony of emerging production techniques of the late 20th century, his sound experiments were swallowed by more purposeful producers. His record as a human being is atrocious and he would eventually die in prison, serving 20 years on a murder conviction. Not a dude worth celebrating.

But what did he accomplish musically? What did he add to Let It Be that McCartney so reviled, the labels so enjoyed, and caused so much polarity? To understand this, let’s look at some of Spector’s unique production techniques on display 1968’s ‘You’ve lost that loving feeling’ by The Righteous Brothers.

The reverb Spector is known for is instantly apparent from the start of the track. The main vocal comes from this haunted, deep place that truly is striking against the powerful baritone. Soon the rest of the track kicks up and we are just swimming in that space.

This custom reverberation, the use of space in recording, was one of the trademarks Spector was known for.

What made his reverb so interesting was his use of custom echo chambers to multiply reverb reflections, a new recording break-thru at the time. A mic might be connected directly into a loudspeaker in a different larger room with just a microphone, increasing the power of the original signal (a natural form of compression) and adding rich layers of reverberation colored by the space. It’s a technique that’s been in use by major studios since.

My critique here is: Spector had no discerning ear for its use. It was his proximity to emerging recording technology that fascinated audiences. Techniques are only techniques when they are rooted in a fundamentally common language, and revolutions are only revolutions when there is artful intention. As we will see, there is never enough intention in Spector’s work.

As we return to our reference track here, try to listen for the tambourine. Once you hear it, try to forget it, with it’s dragging harshness, popping out of the mix with every bang. You hate it because it really doesn’t belong in this space.

Instead of treating every instrument like its own unique presence, Spector just funnels everything through a reverb chamber. The same one, which works for certain sultry tones, but drags the harshness out of others. Notice how every instrument feels far away, but the same amount of far away, making them less discernable. That’s legendary Jazz guitarist Barney Kessel on the guitar, but you’d never know it.

This choice, for less discernibility, for a more stylized, reverb drenched amalgamation of sound, is also a Spector signature. Now, I’ve covered a bit more of this multi-chordal ideal in my article that looks at Debussy and Monk, two huge proponents of extended chords and mashing tones close enough together that new textures emerge. It’s a beautiful concept, and we can cover Spector’s use of it in a later blog (which I also think falls short) but for now we can understand that choosing less clarity in the mixing process was a break in the tradition of producers. Up until this point, clarity was expected in the recording process, and it was a technical game of how to do so better. Spector’s high-profile departure from that norm helped push a new alternative into the mainstream; stylized production.

These two, very specific techniques define the bulk of Spector’s production sound, and they are not just applied sparingly, they are the sound, every time. These signatures, perhaps reflections of the human behind them, are very invasive and violating production techniques. Ones that mangle the recordings to produce new ways of listening that the producer foremost enjoys. You insert yourself in the process basically, making the studio itself an instrument.

Fundamentally I believe in this philosophy; I use the studio as an instrument extensively in my own productions and collaborations with others. However, I am accountable to no-one on my own music, and I work closely with the artists I produce to capture something we both think improves the recording. Making art collaboratively requires creative mutual consent; there would be no meeting of minds between Spector and McCartney.

McCartney had envisioned Let It Be as a return to form for the Beatles, who were on rocky terms with John’s heroine addiction and constant in-fighting. Recordings like ‘Long and Winding Road’ and ‘Let It Be’ show a return to form on pure songwriting. Several of the tracks, including ‘Dig A Pony’ and ‘I’ve Got A Feeling’, were recorded live in their epic 1969 concert on the roof of Apple Records.

When you really start to break apart the bones of the album, McCartney’s intention for a straight-foreword, tight and rebellious sound becomes apparent. The instrumentation is light, the hooks tight, the experimental tones of their granola phase gone; purposeful choices to return their sound to the more edgy Rock feel emerging at the time out of younger artists like The Rolling Stones.

A nod to the emerging Rock movement (as the now seasoned veterans) is the album I believe McCartney envisioned, and it would have been right on the money. The Psychedelic era of the 60’s was waning, over-stylized productions were falling out of favor and wouldn’t regain momentum again until the age of DAWs in the 1980’s. Spector’s sound was spent, and crowds were already turning toward artists like Zeppelin, Floyd and The Stones for a more youthful, raw energy. But, entrenched power structures being what they are, the last person to have ever touched McCartney’s crescendo ended up with it.

Side by Side

To understand the choices and additions Spector made, let’s look at the track that seemed to piss McCartney off the most: ‘The Long and Winding Road’. Try listening to the opening 20 seconds of each right now.

You might be tempted by that powerful swelling of sentimental strings in the Spector cut, and that’s okay. On the surface the track is more busy, and that feels intrinsically stimulating, but try to actually hear the words McCartney is saying, the waiver in his voice as each note lands gently against the piano. You can enjoy that on Let It Be…Naked. After listening to a minute of each, does Spector’s cut begin to feel busy to you? Almost overwhelming, like there is too much going on to concentrate on any one thing?

Why isn’t McCartney’s voice the first thing we’re focusing on? This is the Beatles at their best from a songwriting perspective: subtle, gentle, yet sweepingly beautiful. The quick answer is that Spector inserted himself, his studio, into the process. Let It Be…Naked’s cut uses the same vocal just taken out of Spector’s unnecessary reverb space. In addition to stripping out all of the cheesy sounding instruments, gone is this phony grandeur that accompanied Spector’s overuse of reverb. Instead McCartney’s cut delivers a humble, intricate piece of songwriting.

The first few times I listened to these tracks back to back, I did feel pulled toward Spector’s flashy choices, but eventually I began to see those lavish accompaniments and reverbs for what they were: toxic intruders on this perfectly beautiful sound. And I understood why McCarthy, hated Spector’s cut. I understood Let It Be…Naked.

‘Let It Be’ shows us the power of subtly in the production process. Naked keeps the original piano reverb Spector uses, and rightly so as it’s warm and interesting, but takes everything else out of that sonic space. The hi-hat on Spector’s cut drags in the reverb space louder than anything else, and as the drums come in they push McCartney out. There is again less busy instrumentation on Naked filling the space, and we’ve got more room to enjoy Harrison’s excellent bass work. In fact, everything is simply clearer. The transitions are less jarring without all that noise.

Naked’s ‘Get Back’ dispenses with all the starting fluff, and honestly benefits the most of all the tracks here being mixed 50 years later. Spector didn’t alter too much of this original recording, but he wasn’t the strongest mixer and there are frequency issues Naked is able to correct. Naked also pumps those 50 year old tracks through some modern compressors, which add a lot of body to the sound without distorting. In fairness, that level of clean simply wasn’t achievable in Spector’s time without greater control over the recording process.

Two tracks that are arguably better on Spector’s cut are ‘Across the Universe’ and ‘For You Blue’. With these tracks his little production tricks bring the songs to a more interesting place than McCartney’s straight-foreword take. They aren’t sonically better, Naked again is just mixed better, but they are compelling. With ‘For You Blue’ these differences are negligible, and I’m not sure if they are interesting enough to justify the sonic quality dip.

‘Across the Universe’ is better under Spector, no denying that, but it’s also a track McCartney never intended to be on Let It Be. Spector added in the compilation process, it doesn’t really fit the theme of the album. I feel as though McCartney probably felt shoehorned into including it on Let It Be…Naked. His cut of the song is bare but pretty; it just doesn’t entrance you like Spector’s reverb soaked fantasy.

And While Across the Universe has in retrospect been associated with the Psychedelic era of the 60’s, it’s important to keep in mind that this track reached audiences by 1970, on the dredges of the decades style that was already becoming passé. This isn’t era-defining Beatles; this sound looks backwards to what’s been, not to what will come.

This is ultimately the theme of this longer essay: Spector’s techniques could have been interesting if used in moderation. McCartney initially envisioned a much more straight cut of this album, a return to form, and Spector was the last producer who should have been tasked with that, but the results could have been fascinating had Spector practiced restraint and let the Beatles shine on their own. There are moments, instruments, where his ideas added to the Beatles sound without distracting, but they’re fleeting. Let It Be…Naked reminds us just how invasively he inserted himself into The Beatles sound. It also shows us how unnecessary all of it was; McCartney’s original vision would have made a different kind of impact, possibly more substantial.

Let It Be…Naked, if released in 1970, could have made a better impression with younger audiences. It may have even provided the fuel for the band to burn awhile longer into the 70’s. Every Beatles fan should shudder at that missed opportunity, for their sound to find itself seated in a new decade. I believe McCartney wanted that, and he projected it hopefully into their songwriting and recording process.

But, with or without Spector, Let It Be is still a great album. Production will always be just one piece of what makes an album great, and when the tracks behind it are superb, the results will always resonate with fans. Still, Let It Be…Naked has become the preferred cut on my shelf.