Charles Mingus

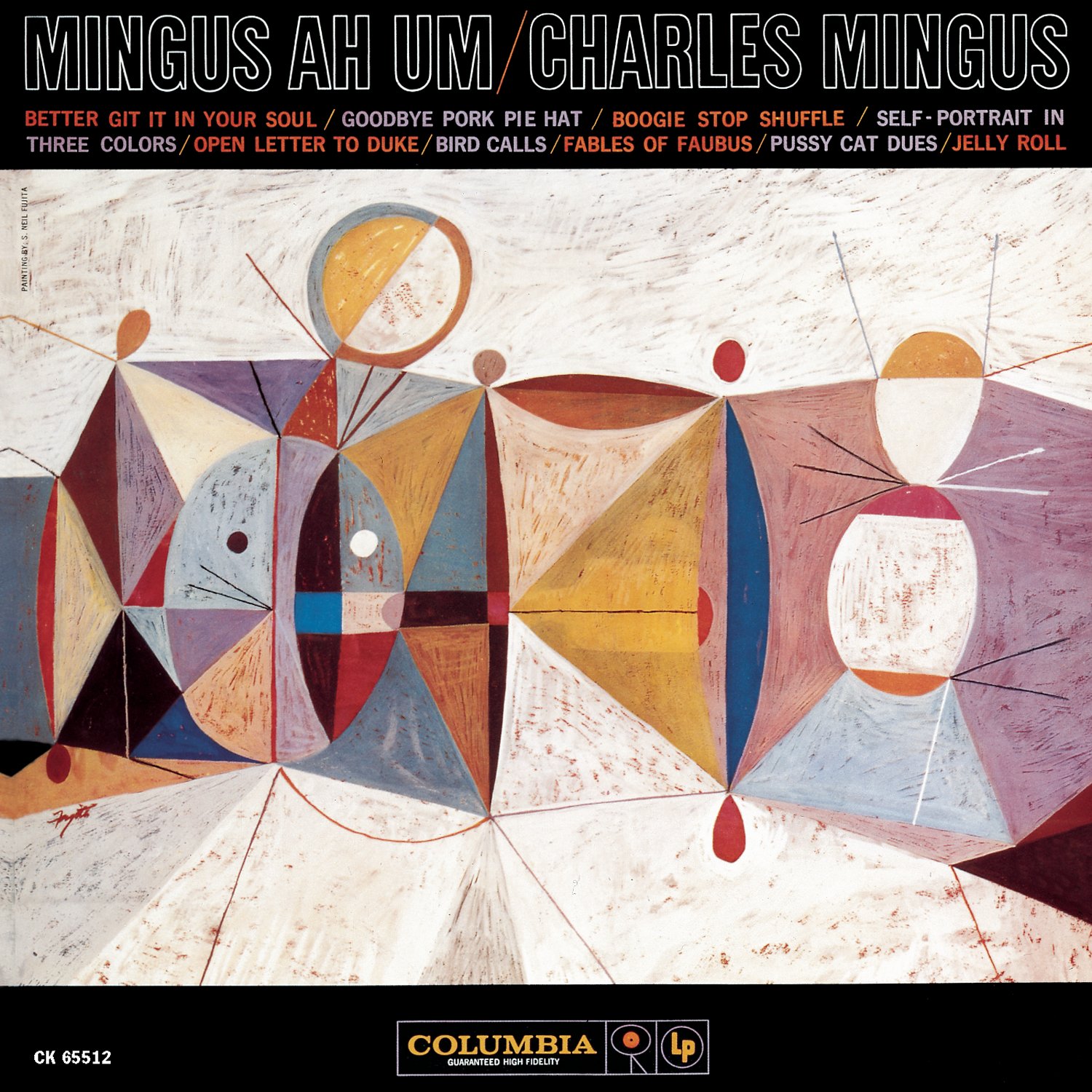

Charles Mingus will always be known for straddling the line of accessibility and the Avant-Garde, a bassist with one foot in each world. By 1959’s Mingus Ah Um, his first for Columbia records and by far one of his finest, Mingus had begun to define a style that would pay homage to the giants of the past while incorporating the spirit of freeform improvisation that was becoming culturally pivotal as we transitioned from the conservative era of the 1950’s.

When we study the emergence of Free Jazz at this time, invariably Ornette Coleman and his legendary album Free Jazz (1960) emerge as the foundational spark of the genre. A direct reaction to the organized and mainstream appeal of Cool Jazz and the 50’s revitalization of Swing for a Sinatra era, Free Jazz was one of many thought revolutions the 60’s brought to American life. It can be tempting to see Coleman’s work as kick starting this decade of free love and thought that would bring us artists like The Beatles & The Beach Boys (and with them, a new reality for American musicians) For my money though, Charles Mingus’s late 50’s work is evidence that the instinct was simmering beneath the surface of musical life, evolving in Jazz innovators long before Coleman’s 1960 work.

Mingus himself was a legendarily insecure performer, lashing out with a violent temper throughout his career and creating needlessly complex song titles that act to reaffirm his own intelligence. He kept a tight control over both who recorded his sound and how. 1956’s Pithecanthropus Erectus, with its heady titles and false intellectualism breathes this insecurity and 1957’s The Clown shows how the 6’4-tall Mingus often viewed himself. The key to Mingus’s brilliance is understand how this self-reflective hatred was channeled to push the conventional limits of Jazz. Brilliant works from this period, like “Haitian Fight Song” (a track that starts with free-form fiddling before breaking into an organized masterpiece) mix Swing with the emerging Soul movement. It creates a piece of music that’s more than just brilliant; it’s aware of its own brilliance, of its own place in time. By lusting after originality, viewing himself as an innovator, Mingus achieves it.

By the time we reach 1959’s Mingus Ah Um, we’re seeing a more complete Mingus, more comfortable in both what he has and what he can contribute to the Jazz cannon. That’s how we arrive at tracks such as “Better Git It In Your Soul” a song from title to sound that evokes the spontaneity and spirituality of early New Orleans Jazz. Midway through, it gives way to a modern, soulful drone in ¾ time, chocked full of vocal vamps, grooving saxophone solos, and block chords that remind us deeply of Horace Silver and his distinctive piano style. From the get go, Mingus tells us that it is less about the players then about the collective sound. He has no qualms borrowing stylistically from contemporaries if it gets him where he’d like to go. It’s this spirt of ruthless originality that sets the stage for the entire work.

“Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is a slowly sensual tune, a mirror of the cool age he’s working amongst. Like “Self-Portrait in Three Colours” it chooses to explore the melodic structure of Cool Jazz rather than reinvent it. For the pieces that actually push the envelope, we must turn towards his homages to both Duke Ellington and Jelly Roll Morton in “Open Letter To Duke” and “Jelly Roll”. Both tracks go out of their way to capture the essence of his heroes while evolving the underlying form. Dannie Richmond keeps the pace tight and chaotic in the right places and irrelevant in others, while tenor sax’s Booker Ervin and Shafi Hadi are perhaps the real break out stars of this Mingus album, made in the shadow of John Coltrane’s rise to the top and the spread of more experimental Jazz.

I have never been able to define Mingus by album the same way we can for an artist like Miles Davis or John Coltrane. Those giants use the album as a vehicle to explore a particular sound, diving in to different facets of it over an hour long project. Mingus, by contrast, does so with each song, creating these pockets of brilliance on an album (which on Mingus Ah Um is definitely the three opening tracks) but also these moments of disconnection, where we look for evolution but only find Mingus retreating into some old cliché. Not every genius hits all the time, and Mingus misses about a quarter of the shots he takes for my ear, but everything he lands transcends.

That is the key to appreciating Mingus, understanding the line between genius reinvention and sloppy combination. Being on either side is not always fluid; sometimes it’s messy and contrite, and all the control and anger in the world won’t convince everyone of your artistic brilliance. Mingus, at his core, is a musician who craved originality and would do anything to get it and maintain it. We just get to come along for the ride.